Mauricio Claver-Carone

Director, U.S.-Cuba Democracy Lobby Group

U.S. policy toward Cuba is frozen in place by a domestic political lobby with roots in the electorally pivotal state of Florida. The Cuba Lobby combines the carrot of political money with the stick of political denunciation to keep wavering Congress members, government bureaucrats, and even presidents in line behind a policy that, as President Barack Obama himself admits, has failed for half a century and is supported by virtually no other countries. (The last time it came to a vote in the U.N. General Assembly, only Israel sided with the United States.)

The news at this point is not that a Cuba Lobby exists, but that it astonishingly lives on — even during the presidency of Obama, who publicly vowed to pursue a new approach to Cuba, but whose policy has been stymied thus far.

The Cuba Lobby isn’t one organization but a loose-knit conglomerate of exiles, sympathetic members of Congress, and nongovernmental organizations, some of which comprise a self-interested industry nourished by the flow of “democracy promotion” money from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The Cuba Lobby was launched at the instigation of conservative Republicans in government who needed outside backers to advance their partisan policy aims. In the 1950s, they were Republican members of Congress battling New Dealers in the Truman administration over Asia policy. In the 1980s, they were officials in Ronald Reagan’s administration battling congressional Democrats over Central America policy.

At the Cuba Lobby’s request, Reagan created Radio Martí, modeled on Radio Free Europe, to broadcast propaganda to Cuba. He named Jorge Mas Canosa,

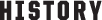

Districts and party composition of the Florida Senate following the 2012 elections. Source

founder of the Cuban American National Foundation (CANF), to chair the radio’s oversight board. President George H.W. Bush followed with TV Martí. Sen. Jesse Helms (R-N.C.) and Rep. Dan Burton (R-Ind.) authored the 1996 Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act, writing the economic embargo into law so no president could change it without congressional approval.

Founded at the suggestion of Richard V. Allen, Reagan’s first national security advisor, CANF became one of the most powerful ethnic foreign-policy organizations in the United States and was the linchpin of the Cuba Lobby until Mas Canosa’s death in 1997. “No individual had more influence over United States policies toward Cuba over the past two decades than Jorge Mas Canosa,” the New York Times editorialized.

In Washington, CANF built its reputation by spreading campaign contributions to bolster friends and punish enemies. In 1988, CANF money helped Joe Lieberman defeat incumbent Sen. Lowell Weicker, whom Lieberman accused of being soft on Castro because he visited Cuba and advocated better relations. Weicker’s defeat sent a chilling message to other members of Congress: challenge the Cuba Lobby at your peril.

In 1992, according to Peter Stone’s reporting in National Journal, New Jersey Democrat Sen. Robert Torricelli, seduced by the Cuba Lobby’s political money, reversed his position on Havana and wrote the Cuban Democracy Act, tightening the embargo. Today, the political action arm of the Cuba Lobby is the U.S.-Cuba Democracy PAC, which hands out more campaign dollars than CANF’s political action arm did even at its height — more than $3 million in the last five national elections.

In Miami, conservative Cuban-Americans have long presumed to be the sole authentic voice of the community, some silencing dissent by threats and, occasionally, violence. In the 1970s, anti-Castro terrorist groups like Omega 7 and Alpha 66 set off dozens of bombs in Miami and assassinated two Cuban-Americans who advocated dialogue with Castro. Reports by Human Rights Watch in the 1990s documented the climate of fear in Miami and the role that elements of the Cuba Lobby, including CANF, played in creating it.

Today, moderate Cuban-Americans have managed to carve out greater space for political debate about U.S. relations with Cuba as attitudes in the community have changed — a result of both the passing of the old exile generation of the 1960s and the arrival of new immigrants who want to maintain ties with family they left behind. But a network of right-wing radio stations and right-wing bloggers still routinely vilifies moderates by name, branding anyone who favors dialogue as a spy for Castro. The modus operandi is the same as the China Lobby’s in the 1950s: One anti-Castro crusader makes dubious accusations of espionage, often based on guilt by association, which the others then repeat ad nauseam, citing one other as proof.

Jorge Mas Canosa, founder of the Cuban American National Foundation

The Cuba Lobby has struck fear into the heart of the foreign-policy bureaucracy. The congressional wing of the Cuba Lobby, in concert with its friends in the executive branch, routinely punishes career civil servants who don’t toe the line. One of the Cuba Lobby’s early targets was John J. “Jay” Taylor, chief of the U.S. Interests Section in Havana, who was given an unsatisfactory annual evaluation report in 1988 by Republican stalwart Elliott Abrams, then assistant secretary of state for inter-American affairs, because Taylor reported from Havana that the Cubans were serious about wanting to negotiate peace in southern Africa and Central America. “CANF had close contact with the Cuban desk, which soon turned notably unfriendly toward my reporting from post and it seemed toward me personally,” Taylor recalled in an oral history interview. “Mas and the foundation soon assumed that I was too soft on Castro.”

The risks of crossing the Cuba Lobby were not lost on other foreign-policy professionals. In 1990, Taylor was in Washington to consult about the newly launched TV Martí, which the Cuban government was jamming so completely that Cubans on the island dubbed it, “la TV que no se ve” (“No-see TV”). But TV Martí’s patrons in Washington blindly insisted that the vast majority of the Cuban population was watching the broadcasts. Taylor invited the U.S. Information Agency officials responsible for TV Martí to come to Cuba to see for themselves. “Silence prevailed around the table,” he recalled. “I don’t think anyone there really believed TV Martí signals were being received in Cuba.

“It was a Kafkaesque moment, a true Orwellian experience, to see a room full of grown, educated men and women so afraid for their jobs or their political positions that they could take part in such a charade.”

Rep. John J. Taylor, (R-P.A.)

In 1993, the Cuba Lobby opposed the appointment of President Bill Clinton’s first choice to be assistant secretary of state for inter-American affairs, Mario Baeza, because he had once visited Cuba. According to Stone, fearful of the Cuba Lobby’s political clout, Clinton dumped Baeza. Two years later, Clinton caved in to the Cuba Lobby’s demand that he fire National Security Council official Morton Halperin, who was the architect of the successful 1995 migration accord with Cuba that created a safe, legal route for Cubans to emigrate to the United States. One chief of the U.S. diplomatic mission in Cuba stopped sending sensitive cables to the State Department altogether because they so often leaked to Cuba Lobby supporters in Congress. Instead, the diplomat flew to Miami so he could report to the department by telephone.

During George W. Bush’s administration, the Cuba Lobby completely captured the State Department’s Latin America bureau (renamed the Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs). Bush’s first assistant secretary was Otto Reich, a Cuban-American veteran of the Reagan administration and favorite of Miami hard-liners. Reich had run Reagan’s “public diplomacy” operation demonizing opponents of the president’s Central America policy as communist sympathizers. Reich hired as his deputy Dan Fisk, former staff assistant to Senator Helms and author of the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act. Reich was followed by Roger Noriega, another former Helms staffer, who explained that Bush’s policy was aimed at destabilizing the Cuban regime: “We opted for change even if it meant chaos. The Cubans had had too much stability over decades.… Chaos was necessary in order to change reality.”

In 2002, Bush’s undersecretary for arms control and international security, John Bolton, made the dubious charge that Cuba was developing biological weapons. When the national intelligence officer for Latin America, Fulton Armstrong, (along with other intelligence community analysts) objected to this mischaracterization of the community’s assessment, Bolton and Reich tried repeatedly to have him fired. The Cuba Lobby began a steady drumbeat of charges that Armstrong was a Cuban agent because his and the community’s analysis disputed the Bush team’s insistence that the Castro regime was fragile and wouldn’t survive the passing of its founder.

The 2001 arrest for espionage of the Defense Intelligence Agency’s top Cuba analyst, Ana Montes, heightened the Cuba Lobby’s hysteria over traitors in government. Armstrong was subjected to repeated and intrusive security investigations, all of which cleared him of wrongdoing. (He completed a four-year term as national intelligence officer and received a prestigious CIA medal recognizing his service when he left the agency in 2008.)

When Obama was elected president, promising a “new beginning” in relations with Havana, the Cuba Lobby relied on its congressional wing to stop him.

Sen. Robert Menendez (D-N.J.), the senior Cuban-American Democrat in Congress and now chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, vehemently opposes any opening to Cuba. In March 2009, he signaled his willingness to defy both his president and his party to get his way. Menendez voted with Republicans to block passage of a $410 billion omnibus appropriations bill (needed to keep the government running) because it relaxed the requirement that Cuba pay in advance for food purchases from U.S. suppliers and eased restrictions on travel to the island.

Sen. Robert Menendez (D-N.J.)

To get Menendez to relent, Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner had to promise in writing that the administration would consult Menendez on any change in U.S. policy toward Cuba.

Senate Republicans also blocked confirmation of Arturo Valenzuela as Obama’s assistant secretary for Western Hemisphere affairs until November 2009. With the bureau managed in the interim by Bush holdovers, no one was pushing from below to carry out Obama’s new Cuba policy. After Valenzuela stepped down in 2012, Senator Rubio (R-Fla.), whose father left Cuba in the 1950s, held up confirmation of Valenzuela’s replacement, Roberta Jacobson, until the administration agreed to tighten restrictions on educational travel to Cuba, undercutting Obama’s stated policy of increasing people-to-people engagement.

When Obama nominated career Foreign Service officer Jonathan Farrar to be ambassador to Nicaragua, the Cuba Lobby denounced him as soft on communism. During his previous posting as chief of the U.S. diplomatic mission in Havana, Farrar had reported to Washington that Cuba’s traditional dissident movement had very little appeal to ordinary Cubans. Menendez and Rubio teamed up to give Farrar a verbal beating during his confirmation hearing for carrying out Obama’s policy of engaging the Cuban government rather than simply antagonizing it. When they blocked

Farrar’s confirmation, Obama withdrew the nomination, sending Farrar as ambassador to Panama instead. Their point made, Menendez and Rubio did not object.

The Cuba Lobby’s power to derail diplomatic careers is common knowledge among foreign-policy professionals. Throughout Obama’s first term, midlevel State Department officials cooperated more closely and deferred more slavishly to congressional opponents of Obama’s Cuba policy than to supporters like John Kerry, the new secretary of state who served at the time as Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman. When Senator Kerry tried to get the State Department and USAID to reform the Bush administration’s democracy-promotion programs in 2010, he ran into more opposition from the bureaucracy than from Republicans.

If Obama intends to finally keep the 2008 campaign promise to take a new direction in relations with Cuba, the job can’t be left to foreign-policy bureaucrats, who are so terrified of the Cuba Lobby that they continue to believe, or pretend to believe, absurdities -- that Cubans are watching TV Martí, for instance, or that Cuba is a state sponsor of terrorism. Only a determined president and a tough secretary of state can drive a new policy through a bureaucratic wasteland so paralyzed by fear and inertia.

The irrationality of U.S. policy does not stem just from concerns about electoral politics in Florida. The Cuban-American community has evolved to the point that a majority now favors engagement with Cuba, as both opinion polls and Obama’s electoral success in 2008 and 2012 demonstrate.

Today, the larger problem is the climate of fear in the government bureaucracy, where even honest reporting about Cuba — let alone advocating a more sensible policy — can endanger one’s career.

Democratic presidents, who ought to know better, have tolerated this distortion of the policy process and at times have reinforced it by allowing the Cuba lobby to extort concessions from them. But the cost is high — the gradual and insidious erosion of the government’s ability to make sound policy based on fact rather than fantasy.

The Cuba Lobby has blocked a sensible policy toward Cuba for half a century, with growing damage to U.S. relations with Latin America. When a courageous U.S. president finally decides to defy the Cuba Lobby with a trip to Cuba, she or he will discover that so too the Cuba Lobby no longer has the political clout it once had. The strategic importance of repairing the United States’ frayed relations with Latin America has come to outweigh the political risk of reconciliation with Havana. Will Barack Obama have the courage to go to Havana?

In October 2011, the St. Petersburg Times and The Washington Post reported that Rubio’s previous statements that his parents were forced to leave Cuba in 1959, after Fidel Castro came to power, were incorrect as they had in fact left Cuba in 1956 during the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. According to The Washington Post, Rubio’s embellishments” resonate with many voters in Florida, who would not be as impressed by his family being economic migrants seeking a better life in the U.S. instead of political refugees from a communist regime.

Rubio responded: “The real essence of my family’s story is not about the date my parents first entered the United States. Or whether they traveled back and forth between the two nations. Or even the date they left Fidel Castro’s Cuba forever and permanently settled here. The essence of my family story is why they came to America in the first place; and why they had to stay.”

Rafael Cruz, Ted’s father, grew up in the Cuban middle class in the 1950s, as the son of an RCA salesman and an elementary-school teacher. As a teenager, he grew to detest the regime of Fulgencio Batista. He and some of his schoolmates frequently clashed with Batista’s officials. Eventually, he linked up with Castro’s guerrilla groups and supported their attempts to overthrow Batista. It’s a decision he still regrets. His move toward Castro, he explains, was mostly due to his anger with Batista’s government, which at one

point imprisoned him and tortured him for his work with the revolutionaries. He says he never shared Castro’s Communism, but, at the time, it was the best way to fight Batista’s oppression. By age 18, in 1957, he knew he needed to get out, and a friend essentially bribed an official to secure him an exit permit.

The son of Cuban immigrants, Menendez has risked the goodwill of the White House and his standing within the party to press the ontinuation of sanctions and travel restrictions against Havana’s totalitarian regime. He riled many of his colleagues by blocking two of Obama’s science nominees and by holding up the 2009 spending measure to protest the Cuba provisions it included.

Diaz-Balart was born in Fort Lauderdale in 1961 to the late Cuban politician Rafael Diaz-Balart. His aunt, Mirta Diaz-Balart, was the first wife of Fidel Castro. Her son, and his cousin, is Fidel Ángel “Fidelito” Castro Díaz-Balart.

Jose Antonio Garcia, Jr. was born in Miami Beach to Jose Garcia Sr. and his wife, Carmen. His parents fled Cuba after the Cuban Revolution occurred and Fidel Castro's Communist regime took power.

Garcia supported the application of a Havana-based research institute to get a license from the U.S. Treasury Department to test and market a diabetes treatment in the United States. Garcia's support made him the first Cuban-American in congress to support a measure that would undermine the

embargo against Cuba. Critics claim that weakening the embargo could eventually lead to giving the Castro regime access to American markets without political reform. Mauricio Font, a Latin America studies expert at the City University of New York said, “This is a ‘wow’ situation. Nothing like this has ever happened In the past, this position would essentially be considered collaborating with the Castro regime.

She stirred controversy by calling for the assassination of Cuban Leader Fidel Castro. She appeared in a British documentary, which was entitled 638 Ways to Kill Castro, saying: “I welcome the opportunity of having anyone assassinate Fidel Castro and any leader who is oppressing the people.” After a 28-second clip began circulating on the Internet, she claimed the filmmakers spliced clips together to get the sound bite. Twenty-four hours after the

controversy erupted, director Dollan Cannell sent unedited tapes of his interview with Ros-Lehtinen to reporters. The uncut version contradicted her response, showing she had twice welcomed an attempt on Castro’s life. Although she attempted to distance herself from her denial, filmmaker Cannell requested an apology.

Albio Sires was born January 26, 1951 in Bejucal, Cuba. He immigrated to the United States with his family at age 11 with the help of relatives in the United States.